If you’ve ever found yourself in a heated argument or witnessed a social media post ignite a storm of outrage, you’ve likely encountered someone trying to pull out what Andrew Perrin, SNF Agora Professor of Sociology at Johns Hopkins University, calls a “superfact.” This is the kind of fact people believe will decisively win an argument—a mic-drop moment intended to silence opposition and prove a point in the ultimate boss fight of public discourse. A superfact might be a statistic supporting your claim, a historical event proving your position or a quote from a respected figure meant to end the debate.

The appeal of the superfact is undeniable. In a world rife with complex problems and sharp divisions, the idea of a single, irrefutable truth cutting through the noise is tempting. Maybe you’ve even tried one yourself. Yet, according to Perrin, searching for superfacts is a distraction: they don’t exist, and the quest for them rarely results in clarity or consensus.

“We spend so much time looking for the one perfect fact that proves our opponent wrong,” Perrin explains, “that we neglect the actual work of argument—explaining, engaging, and understanding.”

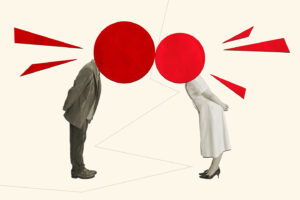

Rather than persuading, the superfact often intensifies tensions. The person presenting the fact assumes they’ve won the argument, while their opponent feels attacked, becoming more defensive. Both sides leave the exchange angrier and more entrenched.

Social media has amplified this dynamic. Platforms such as Facebook and X reward posts that provoke emotional reactions—anger, outrage, or smug satisfaction. A well-timed super fact, delivered with a hint of sarcasm, can quickly rack up likes and shares from those who already agree. However, these viral moments rarely persuade others or foster understanding. Instead, they deepen polarization.

Increasingly, arguments aim less to persuade and more to affirm a group’s beliefs while antagonizing the other side. Though this approach might feel gratifying in the moment, it does little to bridge divides. Perrin describes this phenomenon as “pissing off the right people.”

The impulse for superfacts reflects something positive—a desire for truth and understanding. However, Perrin stresses that pairing evidence with better argument practices ensures they effectively support democracy.

The purpose of a fact, Perrin argues, should be to engage with others across differences—not to dominate or humiliate. He advocates for creating online and offline spaces where debates focus on listening, questioning, and challenging assumptions. Facts should serve as tools for connection and persuasion rather than weapons for silencing opponents.

Education drives this transformation, and Perrin sees colleges and universities as uniquely positioned to teach students how to engage constructively with opposing viewpoints. He envisions programs where students study different perspectives to prepare for debates, participate in structured dialogues, and reflect on their experiences afterward, equipping them not only for democratic participation but also for navigating disagreements in any aspect of life. While extending these principles to the broader public can be challenging, Perrin emphasizes their importance, imagining initiatives such as community seminars in public libraries where people from diverse backgrounds can discuss contentious topics in a respectful and structured way. These forums could provide individuals with the tools to argue productively, counteracting the divisiveness of modern media and empowering them to foster constructive dialogue.

The stakes for democracy are high. When public conversations prioritize emotional validation over understanding, democracy suffers. Arguments devolve into performative boss fights, where the goal shifts from resolution to domination. This dynamic undermines the democratic process, discouraging the open dialogue and mutual understanding essential for a healthy society.

“If we want democracy to thrive,” Perrin says, “we need to stop prioritizing the emotional satisfaction of being right and start prioritizing the hard work of understanding.”

By rethinking how we use facts and encouraging thoughtful argumentation, Perrin offers a hopeful vision for the future. Evidence doesn’t have to be a weapon; it can serve as a bridge. With a shift in focus, public discourse can move away from superfact-driven divisive battles and toward building a stronger, more connected democracy.